Executive summary

- Increased resilience. The Latin American region is dealing remarkably well with the triple shocks of the pandemic, Russia's invasion of Ukraine and rising US interest rates. The region's GDP is now firmly above its pre-pandemic size. This underlines the region's much improved resilience since the financial crisis of the 1980s, on the back of stronger macroeconomic policy frameworks, improved banking supervision, and higher official reserves. Compared to other global regions, the Latin American region is more resilient to a downward global scenario of tightening global credit conditions. The main exception among the region's larger economies is Argentina.

- Weak outlook. Meanwhile, the region's outlook has worsened. This reflects global headwinds, tight financial conditions and political uncertainty in many countries. Growth will recover somewhat next year as these headwinds fade but will remain weak due to structural impediments. The recent arrival of El Niño adds to the region's challenges. As a result, Latin America and the Caribbean will once again lag the rest of the emerging market regions.

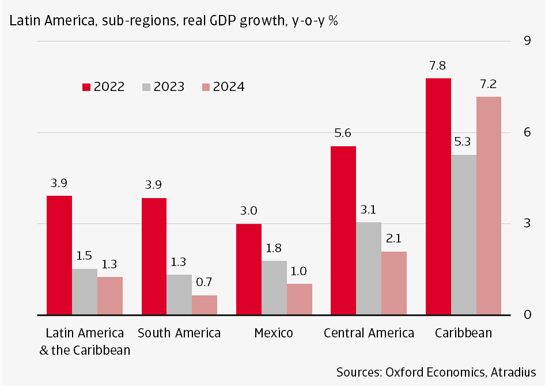

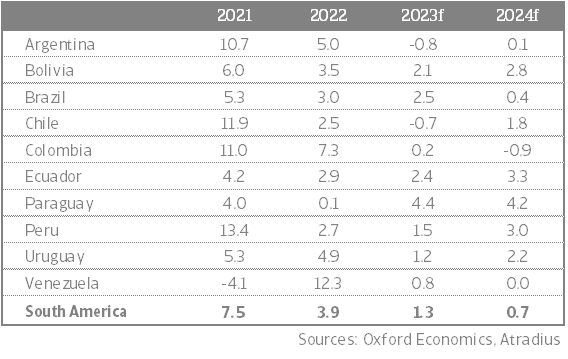

- The region's largest economies are facing particularly weak growth prospects. As these are mainly located in South America, this sub-region will show the poorest performance. The economies of Argentina, Chile and Colombia will contract in 2023 or 2024. Central America is expected to see steady growth. This is also the case for Dominican Republic, making it the exception among the region's larger economies. The smaller economies in the Caribbean will show the fastest growth, but most of their economies, particularly the tourism dependent countries, are still below their pre-pandemic levels.

Improved robustness in the face of many challenges

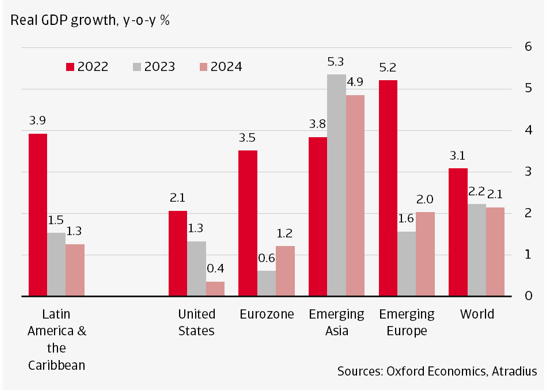

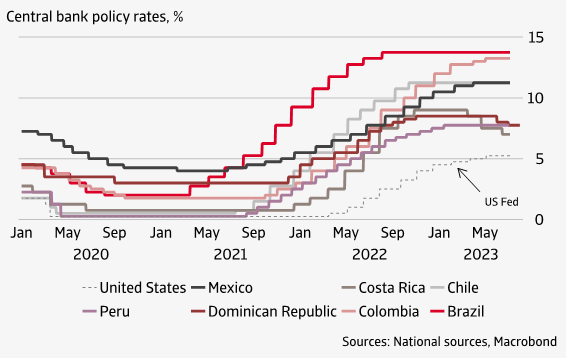

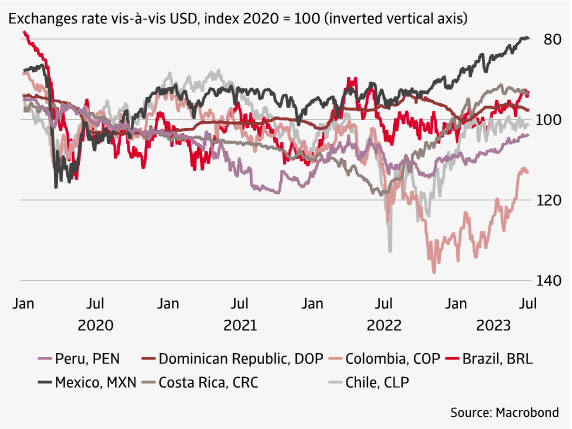

Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) is dealing remarkably well with the triple shocks of the pandemic, Russia's invasion of Ukraine and rising US interest rates. Real GDP grew 3.9% in 2022 and the region's GDP is now firmly above its pre-pandemic size. This underlines the region's much improved resilience on the back of stronger macroeconomic policy frameworks, improved banking supervision, and higher official reserves. Since the debt crisis in the 1980s – often referred to as the lost decade, which continued for some into the 1990s – many countries in Latin America moved towards flexible exchange rate systems. The latter allows the currency to be used as a shock absorber and enhances monetary policy autonomy. Furthermore, many have introduced fiscal rules and made their central banks independent. The fact that the region’s central banks were among the first movers to hike interest rate in response to rising prices since 2021 is evidence of this improved policy framework.

Meanwhile, the region's outlook has worsened. We forecast GDP growth to slow to 1.5% in 2023 and to remain sluggish at 1.3% in 2024, lagging other emerging market regions. This slowdown mirrors the deterioration in the external environment, especially in key trade partners, the US and China. Skyrocketing inflation in the US and the Federal Reserve’s monetary tightening response both pose headwinds to global economic activity. Although China's economy is recovering after the late lifting of that country’s zero-Covid policy, its industrial production remains meagre and as such the demand for commodities. Lower demand for goods as well as travel from advanced economies and less production in China will keep Latin America’s economic growth below its pre-pandemic annual average of 2.5% over the coming years.

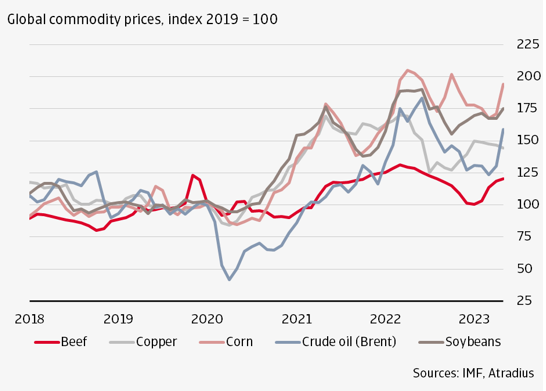

Commodity prices also pose an external drag on growth. The price of major commodities that Latin America and the Caribbean produce rose significantly from the pandemic through last year as global demand recovered. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and adverse weather conditions raised energy and food prices as well. While the impact of higher food prices on the major food exporting countries was muted as adverse weather conditions suppressed yields, higher energy prices provided some boost for oil exporters like Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana and Trinidad & Tobago that will fade in 2023 with prices more than one third lower around USD 75 per barrel Brent. Of course, the easing of oil prices does offer some relief, especially for those countries dependent on energy imports like in the Caribbean. Lower energy prices will help slow down inflation, easing pressure on consumers. But food prices are set to remain high with risks to the upside, especially associated with El Niño (see in focus box).

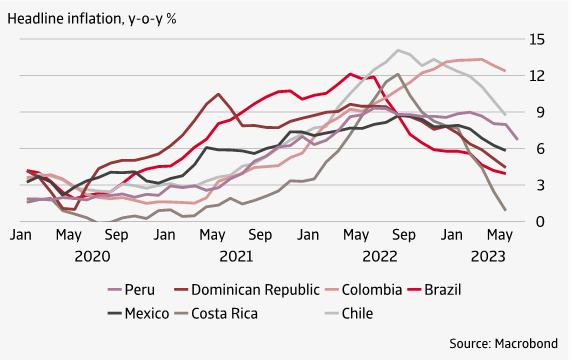

This brings us to internal factors explaining the meagre growth outlook for the region: still elevated inflation and the impact of tight financing conditions. To analyse the key regional trends here, we focus on the largest LAC economies with the addition of Costa Rica which recently joined Chile, Colombia and Mexico as an OECD member in the region.

Inflation appears to have peaked in most LAC countries but it’s clear that we are not out of the woods yet (see figure 3). Inflation remains well above target in most markets – with the exception of Costa Rica – and risks remain to the upside, particularly for food prices. This will delay monetary policy easing.

As mentioned in this section’s introduction, the region's central banks hiked interest rates earlier and more aggressively than the US Fed to fight inflation stemming from rising food and energy prices which was exacerbated by Russia's invasion of Ukraine (see figure 4). But core inflation, which excludes food and energy, remains stubbornly high above pre-pandemic levels and is only expected to decrease more sharply through the year given the lagged impact of monetary policy. On top of this, recent global financial volatility further deters a general monetary easing cycle. While the central banks of Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic felt confident enough about the disinflation process to start its monetary easing cycle in March and May of this year respectively, the region’s other largest economies remain in wait-and-see mode. This will continue to drag on domestic demand, keeping growth prospects muted in 2023 and 2024.

Next to the weaker external environment, elevated prices and tight financial conditions, the lacklustre economic outlook is due to policy uncertainty, limited room for fiscal support and most of all structural problems. Policy uncertainty is related to shifts in government in many countries over the past years. This reflected voters' discontent about drugs-related crime and violence and high inequality in income and access to healthcare and education, factors that also fuel social unrest. Policy uncertainty, social unrest combined with a challenging business environment constrain investments and the region's growth potential. These structural factors also explain the region's low global integration which makes it challenging for the region to benefit from nearshoring – a topic that we will explore more in depth in an upcoming research note.

All-in-all, growth prospects are particularly weak in the region's largest economies. South America is the slowest growing sub-region (see figure 5) and Mexico is also facing meagre growth. Higher prices and the slowdown of the US economy are weighing on Central America’s outlook as well. The Caribbean will keep its place as the fastest growing sub-region, with its largest economy, Dominican Republic, continuing with steady growth. Guyana will be the fastest growing economy in the western hemisphere over the forecast period as new oil production coming online ensures GDP growth above 35% per year.

To end on a positive note, much improved resilience will help most of the countries in the region to steer through this challenging environment. In fact, our modelling in the most recent Atradius Global Economic Outlook shows that Latin America is the most resilient region to our downside global scenario of more persistent inflation and tighter credit conditions. This improved shock resistance is also what markets expect: the currencies of the region’s largest countries among the world’s strongest (see figure 6), despite a narrowing interest rate differential vis-à-vis the US. The most vulnerable countries are Argentina, Bolivia, Cuba, El Salvador and Venezuela – which have weak policy frameworks and low official reserves – and the smaller, less diversified islands in the Caribbean.

South America: slow growth, high policy uncertainty

After a stronger than expected performance in 2022, we project economic growth in commodity-rich South America to fall from 3.9% in 2022 to 1.3% in 2023 and to ease further to 0.7% in 2024. This makes South America the weakest performing sub-region in Latin America. Next to a moderation of external demand and commodity prices and the lagged effects of high inflation and monetary policy tightening, country-specific factors weigh on South America's growth prospects. The region continues to deal with the effects of a wave of social unrest starting in late 2019, particularly in Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile, Colombia and Peru. Higher food and energy prices contributed to social pressures as well. This, combined with elevated policy uncertainty and governability challenges will undermine business sentiment and private investments in most of South America going forward.

Droughts contribute to social pressures

Periods of droughts are common in Latin America. They relate to the two opposing El Niño (warming) and La Niña (cooling) climate patterns in the Pacific Ocean that can affect weather worldwide causing heavy rainfall or droughts. But climate change also plays a role as it has increased the frequency, intensity and duration of heatwaves, reducing water availability and worsening the impact of droughts. Latin America is particularly vulnerable to such droughts, not just for its food production, but also for its electricity (mainly hydropower) and river transportation.

Central Chile is since 2010 experiencing a ‘mega drought’ due to which over half of its population lives in an area suffering from “severe water scarcity”. This puts Chile at the forefront of the region’s water scarcity; Mexico is in second place.

A three-year – unusually long - La Niña (2020-early 2023) resulted in a severe drought in Northern Mexico and southern South America, home to some of the world’s largest producers of soy, corn and beef. Of these producers, Argentina was hit the most and to a lesser extent also Brazil (in 2020/21), Paraguay and Uruguay.

While La Niña has officially ended in March 2023, El Niño has arrived and is likely to persist until 2024, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) recently declared. This will bring – heavy - rainfall in South America's tropical west coast and Argentina, but droughts to the north-eastern part of South America, the mid-centre of Brazil (where over 70% of its electricity is generated) and to Central America and the Caribbean.

The upcoming drought would add to food affordability challenges. In most of the countries affected, food price inflation is already high between some 10%-17% in Central America (Panama being the exception) and some 14%-18% in Chile, Colombia and Peru in April 2023. Moreover, it could result in food availability problems. The most vulnerable countries are those with relatively low income and where drier-than-average weather conditions affect the entire crop cycle. This puts lower middle-income countries in Central America and the Caribbean at food security risk.

Finally, the upcoming drought could lift the region’s social pressures. Water scarcity was an important factor driving protests in Chile and Northern Mexico. And research shows a correlation between droughts, food accessibility and availability, and urban conflict in the Central American Dry Corridor, an ecological zone stretching from Southern Mexico to Panama.